Frontiers of Change

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

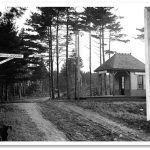

| First Meeting House, Albert Hudson painter (SHS) |

As Sudbury became an English frontier settlement in the mid-1600s, it seemed to European settlers that they were moving into an untended, unoccupied region that was full of potential and almost empty of other inhabitants. An early Sudbury land deed described one large land tract by naming Anglo owners on three sides, but gave up on the fourth side, describing it simply as “butting on the west(,) the wilderness.”

What the English settlers saw as wilderness was already home to a permanent population of one or more Nipmuc and Wampanoag tribal groups. King Philip Woods, located between an ancient indigenous trail and the Sudbury River marshes, is likely the area where at least one indigenous family or clan group lived before Anglo settlement; they would have traveled to this area on ancient trails that followed much the same path as today’s Water Row (extends to River Road in Wayland).

The Nipmuc had cleared small planting areas in Sudbury’s fertile floodplain; they had managed forest edges by controlled burns to encourage the shrub growth that would attract game. They had also traveled downstream to the drumlin now called Weir Hill, where they built traps to catch shad and alewife in a seasonal harvest. There is no evidence that the Nipmuc permanently altered the landscape over the thousands of years that Nipmuc people and they occupied this land and considered it the closest part of their broad homeland.

The “wilderness” that Anglo settlers perceived was largely due to the two cultures being guided by dramatically different beliefs about the value of land and its appropriate uses. The Nipmuc, and broader Algonquian tradition, was one of respect for the wild and its gifts to humans. The wild land and waters around them provided what they needed to sustain life without their impinging on future generations’ use of the same resources.

By contrast, although the Anglo-European mindset celebrated the land as god-given as did the Algonquian, the settlers believed that their god charged them that the land be improved for god’s glory. Practically, this meant that land and water resources should all contribute to the improvement of humanity. Settlement should spread; broader areas should be cleared for agriculture; trees should be cleared for housing and workable land; animals should be trapped or shot to make a safer settlement environment.

A whole body of English law concerned itself with property rights and limitations. A basic tenet of it was that once a parcel of land was defined and legally purchased, the new owner (a “freeman”) or owners (a town or “plantation”) held the property for their use only. They had exclusive use of that property. Two centuries of war and Indigenous disenfranchisement grew from the clash between the English definition of responsibility to “improve” the land, and the Algonquian belief that their people did not so much own the land as borrow use of it during their lifetimes. Thus use of land could be shared, but it was not theirs to literally give away.

The conflicting views of indigenous people and colonists regarding changes in the use of the land caused much discord, leading to King Philip’s War (1675-1676). Sudbury was one of the towns directly affected by the conflict. On April 21, 1676, the town was attacked by a combined force of Nipmuc, Wampanoag and Narragansett warriors but, despite initial success in penetrating the town’s defenses, the indigenous forces were eventually repelled by colonial militia. The Sudbury fight marked a pivotal moment in this deadly conflict, convincing British colonial authorities of the necessity to fortify New England’s frontier towns and bolster defenses against all local tribes and indigenous settlements.

The period between Sudbury’s settlement in 1639 and at least the early 1800s was a frontier of change for the Nipmuc residents of the area. They confronted a wilderness of new cultures and beliefs, a hostile human environment, new living conditions, and prejudice against their lifestyle. They did not vanish from the face of the earth, as numerous historians claimed, but by the mid-19th century the roster of Sudbury residents no longer included identifiable Algonkian names, as Hudson writes in his 1890 history:

| “But, as years passed on, they grew rapidly less, even at this their old mission home. The last family hereabouts has long since disappeared, their name is unspoken, and their very graves are unknown.” |

How the Landscape Was Transformed

The landscape of New England underwent significant transformation following colonization by Europeans in the 17th and 18th centuries.

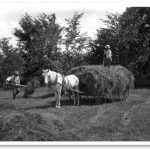

Clearing of Forests: One of the most noticeable transformations was the widespread clearing of forests to make way for agriculture, settlements, and timber extraction. The clearing of large swaths of land for farming resulted in the creation of open fields and pastures where dense forests once stood. European agricultural practices, including the cultivation of crops such as rye, corn, and hay, significantly altered the landscape. Some fields were fenced or later, walled in, for pasture as livestock grazing became widespread, leading to further changes in land use patterns and the fragmentation of habitats. By 1880, 60-80% of southern New England forests had been cleared for pasture, tillage, orchards, and buildings.

Introduction of Non-native Invasive Species: Colonists brought with them many, plants and animals that were native to their homelands, including field crops, livestock and ornamental plants. This introduction of non-native plant and animal species had profound ecological consequences for Sudbury’s landscape. Many non-native species quickly became established and often outcompeted native species. Invasive plants such as English ivy and Honeysuckle took over disturbed habitats, displacing native vegetation and altering ecosystem dynamics. Similarly, introduced species like the European starling thrived in the new human-dominated landscape, competing with native wildlife and disrupting ecological balance. Today, these species have proliferated throughout Sudbury. Click here to learn more about Sudbury’s invasives species and how you can help in the effort to control them.

Trail to Roads: Indigenous paths played a crucial role in shaping the landscape and transportation network of colonial roads. Colonial settlers recognized the practicality and efficiency of utilizing existing trails, which often traversed the landscape along the easiest routes, avoiding obstacles like dense swamp land or steep terrain. In Sudbury, Concord Road, Boston Post Road, Old Berlin Road, Water Row and Old Lancaster Road likely follow the paths of original indigenous trails. The map below shows the network of roads as it existed in 1795 (Mosmon), when Sudbury extended east of the Sudbury River.

Plan of Sudbury surveyed by Mathias Mosmon dated April 17, (later print edition)

Construction of Mills and Dams: The need for water-powered mills led to the construction of dams and millponds along rivers and streams, altering the natural flow of waterways and impacting aquatic ecosystems. Mills were used for grinding grain, sawing lumber, and processing textiles.

More about King Philip Woods, Water Row, Nobscot Hill

The ancient trail that became Water Row was also the vicinity of some of Sudbury’s earliest English homesteads, including the Haynes Garrison House. Upslope from the Haynes property, overlooking the Sudbury River marshes, archeological evidence has identified one or more indigenous living sites in the area of King Philip Woods. Over the next century, as colonists took over the level Indigenous planting fields near the river and cut down much of the surrounding forest, some Nipmuc families resettled in more strategic, but much less hospitable, territory such as Nobscot Hill. A hike up Tippling Rock Trail on Nobscot Hill gives a feel for the steep and rocky terrain. (See also Setting the Post Glacial Landscape page.)

Places to experience Sudbury’s Indigenous Landscape

| Look for indigenous trails such as Water Row, which extends to River Road in Wayland. This was the vicinity of some of Sudbury’s earliest English homesteads including the Haynes Garrison House, which bore witness to the Sudbury Fight on April 21, 1676. The house site and entrance to King Philip Woods can both be found along Water Row, near the intersection with Route 27. Water Row and River Road, which extend north and south of Route 27 along the Sudbury River, provide spectacular views of the vast, unspoiled Sudbury River floodplain. A number of car pull-offs are available along the road. |

|

Water Row

|

Milkweed at the Sudbury marshes (EKT)

| Located on the southwesterly side of Water Row King Philip Woods and the Haynes Garrison House site can be explored on foot. The area surrounding King Philip Woods (named after Wampanoag leader Metacom, whom the English called “King Philip”) was once part of the traditional territory of the Nipmuc. The landscape would have provided abundant natural resources, including game animals, fish, edible plants, and materials for crafting tools and shelter. Additionally, the proximity of the Sudbury River would have offered opportunities for fishing and transportation. A trail leads from King Philip Woods to the Haynes Garrison House. Parking is available on Old Sudbury Road near Wolbach Road, as well as at a small gravel pull-off on Water Row. All that is still visible in the landscape of this dramatic shift in Sudbury is the cellar hole of the Haynes Garrison House located on Water Row. Constructed in 1640 by Deacon John Haynes, the Haynes Garrison House served as a fortified dwelling designed to provide protection for neighboring settlers during times of conflict. Below is a sketch provided by the Sudbury Historical Society (SHS) of the Haynes Garrison House and a photo of the site today. The area provides diverse topography, a small pond, a bog, and several interesting historic foundations. Click here for a trail map and more information on King Philip Woods. |

|

|

| Artist Rendering of Haynes Garrison House (SHS | Haynes Garrison Ruins (SCC) |

| Located on Route 20, in the western part of Sudbury, Tippling Rock Trail ascends to a rocky overlook across the valley with views of Boston. Steeped in folklore, Tippling Rock was an important destination for Sudbury’s native people and remains a recreational destination for Sudburians today. Tippling Rock is also an attraction along the 230-mile Bay Circuit trail running from Plum Island to Duxbury. Click here for a trail map and more information on Tippling Rock. A small gravel parking lot is available on the south side of Route 20 between Dudley and Nokomis Roads. |

|

Vista From Tippling Rock (SCC)

| Located on Brimstone Lane, Nobscot Conservation Land and the adjacent Nobscot Scout Reservation was named by indigenous people. Nobscot, or Penobscot as originally named, means “place of falling rocks” in the Algonquian language, and was considered sacred space. It became a refuge for a small group of Nipmuc when colonists took over many of their lands closer to the Sudbury River. In later years, colonists homesteaded here, and turned some of the land into pasture for livestock. Click here for additional information on Nobscot Conservation Land and a trail map. Also see Lands of Indigenous Peoples page for more information on the Nobscot Hill complex. |

Return to homepage or click on photos at top of page to explore other eras of change.