Smooth River, Small Falls

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Boating on the Sudbury (SHS) |

Sudbury’s brookside and river meadows had always been reliable sources of hay for the town’s farmers, and a broad natural environment for fish and waterfowl. During the 19th century, dams downstream increasingly flooded meadows along the Sudbury River, while discharge from other mills upstream began to degrade the town’s water quality.

New residents put new demands on housing stock. Farms were turned into house lots bought by Boston commuters, and multi-family housing was built for mill workers in South Sudbury’s Mill Village.

|

Parmenter Mill in South Sudbury, ca. 1910 (SHS)

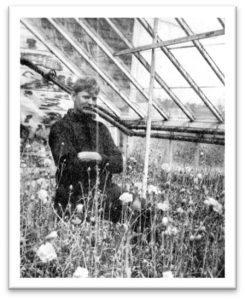

Some farms, especially along the broad Route 20 swath of floodplain, created a longer growing season with greenhouse production of vegetables and flowers for new urban markets.

The Local Scene

The changes that happened to Sudbury’s land in the course of 100 years exemplify the far-reaching impact of New England’s first era of modern industrial development.

A 1795 map of Sudbury included this comment by cartographer Matthias Mosmon about milling on Hop Brook:

| “No manufactories are erected in Sudbury, in sd [town] are three grist mills, two saw mills, and one fulling mill as above described, on a Stream known by several different names.” (quoted in Alfred S. Hudson, History of Sudbury, 1889 |

In the early 19th century Sudbury was still not a place known for industry, primarily due to its lack of waterpower. Winding Hop Brook did have small waterfalls that could be controlled by relatively simple wood and earthen dams. Each dam held back some amount of water in a small mill pond like that at the Wayside Inn. The brook was a reliable source of power for local saw mills that cut lumber from the Nobscot forests and for grist mills that ground local farmers’ harvests into rye and barley flour, corn meal, and coarse-ground fodder. Lumber and flour had been sold and traded since Peter Noyes built the first Sudbury grist mill in the 17th century. Other sites along the brook hosted tanning mills (for animal hides) and fulling mills (to finish woven woolen cloth) that called for moving water but required little water power.

|

Mill Village: 1830 Map of Sudbury, drawn by William Wood

The Sudbury River, on the other hand, was virtually useless for any kind of industry. It was too flat. Along the whole course of the river through town the change in water height was nearly immeasurable. Hudson comments:

| “It is said to [fall] but two inches to the mile for twenty-two miles.” (A. S. Hudson, History of Sudbury, 1889) |

Significantly, the persons who said that were eastern Massachusetts’ best-qualified surveyor Loammi Baldwin, in 1811, and in 1834, passionate river advocate and surveyor Henry David Thoreau. This means the river falls slightly less than four feet total between Saxonville and Billerica. (Robert Thorson, The Boatman, 2017)

For a modern comparison, the fall of water in Framingham alone between the Saxonville Mills and other industries through town is over 32 feet.

If Sudbury’s geology had been different, Sudburians might have constructed a dam to increase the fall, and thus the waterpower, of their river, but the broad soft-bottomed wetlands and flood plain that flank almost the entire length of the river made such construction impossible. It was also likely undesirable to a town of farmers who relied on the river meadows for marketable hay, autumn forage for cattle, and rough bedding for their barns.

Sudbury River Context

The Sudbury River flows north along the entire east side of Sudbury. It then passes into Concord where it encounters the narrow, southeast flowing Assabet River. Here, the two rivers combine to form the Concord River, which flows more swiftly and heads northeast, eventually falling (literally) downward off the coastal plain into the Boston Basin and out to sea. Along the way the river draws itself in and passes through a rocky narrow, tumbling over ledges before it merges with the Merrimack and settles down again in its flow to the sea.

The rocky narrow is in Billerica – only two towns downstream from Sudbury as the river flows – the site of a dam since as early as 1711, powering small mills not so different from those in Sudbury. But after the American Revolution, as the new United States worked to unify its isolated towns and villages, the (revolutionary!) Middlesex Canal Corporation replaced the river’s colonial dam in 1811 with a higher one to divert water into the canal. Twenty years later that dam was raised and enlarged again in order to power the Talbot Woolen Mills, a complicated group of buildings and functions. All those functions required the enhanced waterpower provided by a 10-foot high dam in order to keep machines running year-round – even through periods of drought.

What Does This Have to Do with Sudbury’s Land??

From their earliest days, the woolen and cotton mills that developed on the Sudbury River at Saxonville discharged the ‘dirty’ water that resulted from their manufacturing processes into the River, where it flowed downstream toward Sudbury. Significantly, later mill owners dumped “heavy metals” into the Sudbury that still prevent this classic fishing stream from being approved as providing edible catch.

More importantly, the impact of the Talbot dam on the Sudbury grasslands, which was located upstream of the Middlesex Canal and Talbot Mills, was so significant that it was the subject of a Massachusetts legislative inquiry in 1861. Farmers from Sudbury, Wayland, Concord and Bedford testified to the changing conditions and to the reduced market value of land near. this natural resource, due, it appears, to the height of the dam in Billerica. Sudbury historian Alfred Hudson quotes from the legislative report:

| “William Stone [born ca 1787]. “I bought, forty-three years ago, a meadow on the Sudbury River,…. When I bought it I used to get the hay almost every year. There were two acres of shore, and the rest, where the water came on, was such a meadow as I never saw, producing pipe and lute grass. I used to get a ton and a half per acre. I used to drive across the meadow to water my team. I mowed it about twenty years; I began then to find the water came over. I built a causeway across, but the water seemed to stay. I tried to pole the hay out [remove by barge to dry land], but it cost too much. I sold it for $110 for eleven acres. At first it was worth to me $80 per acre. The water seemed to go away only by evaporation. … I have seen cattle getting fall feed on the meadows; not even a man could now go there without miring.”(Alfred S. Hudson, History of Sudbury, 1889) |

|

|

| Courtesy of Wayland Historical Society, Haystacks on the Sudbury River ca. 1890-1899 (Alfred W. Cutting). WHS ID #2 All rights reserved. | Flooded Hay Fields (Hattie J. Goodnow) (SHS) |

Despite legislation, the dam was apparently never lowered. Sudbury’s Broad Meadows and the wide reaches of wetland and swamp we see today are a result of industrial development 22 miles away. Hudson optimistically commented that there had been an improvement in fishing opportunity, but he wrote that before the “fishway”, or ladder that had been required when the higher dam was built, was concreted over in the 1960s, effectively preventing diadromous fish from spawning in the upper reaches of the Sudbury River.

| Sudbury River Floodplain (SVT) |

Agricultural Evolution

The small industries on Sudbury’s Hop Brook were not substantially affected by this dramatic change in the Sudbury River. Hudson briefly describes those that were enlarged or built in Mill Village during the 1800s:

| “The industries of South Sudbury have been various. In 1794, besides the saw and grist-mill run by Cutler and Holden, there was a fulling-mill run by Mr. Reed. About three-quarters of a century ago [ca 1815], bricks were made at the Gibbs place and also at the Farr farm.….Leather was tanned by William Wheeler at a place just beyond the bridge…. There were also tanning vats on the “Island”. ….About 1850, William Jones and Theodore Brown had a shoe manufactory…. Since 1850, shoe tacks and nails were made at the mill by Calvin How, and hats and leather board by Rogers and Moore.” (Alfred S. Hudson, History of Sudbury, 1889) |

South Sudbury’s Mill Village became the town’s major commercial area not because of its own 19th century industrial growth as much as its cross-roads and cross-rails location. It was a connector site between growing industrial centers at all points of the compass.

Writing his History in 1889, Hudson also takes time to recognize what was becoming Sudbury’s most important commercial enterprise. It was an evolutionary fusion between farming and indoor horticulture. Some farms, especially along the broad Route 20 swath of floodplain, created a longer growing season with greenhouse production of vegetables and flowers for new urban markets. The “hot houses” were less impacted by weather or unpredictable river flooding, while the farmers could also count on a longer and earlier growing season.

|

James Howell Bartlett and his Glass Greenhouse (SHS) |  |

| This was still farming, but farming relying on industrial models to be efficient – and profitable. Hudson comments: |

| “The main business in and about South Sudbury has been farming. Of late years, early gardening has received much attention and greenhouses have been used by some. The first greenhouse in Sudbury was erected in 1879 by Hubbard H. Brown for raising cucumbers. He has since erected three more, all of which cover six thousand feet of ground. Since 1882, thirty greenhouses have been built. There is now used for raising vegetables and flowers nearly one hundred thousand square feet of land covered with glass. Fifteen farmers and gardeners are engaged in the work. It is estimated that seven hundred tons of coal are consumed yearly, and about fifty thousand dollars are invested in the business. The buildings are all heated by hot water except in one instance where steam is used. Most of these are used for raising vegetables, such as cucumbers, lettuce, rhubarb, tomatoes, etc. One house has twenty-eight thousand lettuce plants, another has twelve thousand carnation pinks.” |

After the Civil War and well into the 20th century, Sudbury also saw a notable population increase. Some newcomers worked for area farmers; others commuted to work elsewhere on the two railroads that came through town after 1870. (See Rural Town to Western Suburb page)

The contrast is dramatic: 1800 Sudbury had counted 205 households in the entire town. A century later, that number had grown to over 300. About a third of Sudbury’s households were renters, not owning their homes; they lived in leased houses or rooms rented in family homes. Either way, the new residents put new demands on housing stock. Some farms were turned into house lots bought by Boston commuters, and multi-family housing was built for mill workers in South Sudbury’s Mill Village. The little rural town of Sudbury was on its way to suburbanization and would soon require more and better roads, schools, civic improvements and a tax base to support them.

Where to explore – turn on your imagination for this one!:

| The intersection of Route 20 and Concord Road marks “Mill Village”. The final falls on Hop Brook are behind trees; new buildings and parking lots replace the 19th century grist and saw mills and the craft shops. Drive west to 578 Boston Post Road where J. P. Bartlett greenhouses remain as testament to the once thriving agricultural district on this road. On nearby Codjer Lane, off Union Avenue, Cavicchio Greenhouses are another survivor. |

| Park at Mill Village marketplace and follow the sound of water to the Hop Brook falls. Imagine buildings noisy with workers and machines. On the Boston Post Road (Route 20) look for houses from the 1700s and early 1800s, built for earlier artisans. |

Return to homepage or click on photos at top of page to explore other eras of change.