Lands of Indigenous People

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As glacial Lake Sudbury receded, it formed Hop Brook and the Sudbury River valleys, both rich natural resources, while the river was also a watery trail for humans with canoes. Glacial action had turned stone to sand and dirt to clay, revealing a habitable landscape. Over 12,000 years, as the climate warmed to more moderate temperatures and weather patterns, Sudbury’s barren landscape filled in with plants and trees, soil and insects, reptiles, fish, birds, and mammals. Indigenous presence in Sudbury dates back to at least the Middle Archaic Period (8,000 – 6,000 B.P.) with seventy confirmed archeological sites from that time through the Contact Period (1500-1620 A.D.). Well before the Contact Period Sudbury was largely forested, with stretches of natural river meadow and small cleared fields used for agriculture. Unlike today’s forests, sizable patches of pre-contact forest land were devoid of understory brush and fallen branches, as inhabitants cleared out dead wood for hearth fires and practiced regular controlled burns to assist in hunting. Animal populations were bountiful and diverse and included many species still present today, like deer, fox, beaver, waterfowl, and predatory birds. These forests also harbored species no longer present such as apex predators like the wolf, extirpated from the area by 1840. Indigenous people maintained a deep connection with the wildlife that inhabited Sudbury and the surrounding area. Over thousands of years, the Nipmuc and their ancestors had developed and shared intricate knowledge of the local ecosystem, including behavior patterns and habitats of various species – necessary information for people who relied heavily on wild animals and plants to supplement the crops grown in their gardens. Plants were regarded as teachers and healers, offering valuable lessons on resilience and adaptability. The indigenous approach to land and wildlife management was underlain by respect for natural balance and sustainability. The Nipmuc used what we label today as “sustainable land management techniques”: controlled burns to manage woodland underbrush; selective hunting and gathering, and agricultural crop rotation. The techniques were practiced to maintain a healthy ecosystem and a balance between human needs and the needs of other species. To indigenous people, the land was imbued with spiritual significance. Many natural features were seen as manifestations of ancestral spirits and deities. Hills, rivers, and forests held deep spiritual meaning. Central to the indigenous perspective on land in Sudbury was the concept of stewardship, recognizing their role as caretakers entrusted with the responsibility of safeguarding the land for all species and for future generations. This stewardship ethic encompassed practices of conservation, preservation, and communal land use, reflecting a collective understanding of interconnectedness and interdependence among all living beings. An example of contrasting views on the interaction of wildlife and the land is the beaver, an animal that has had a profound impact on Sudbury’s landscape that continues to do so today. In the 1800s, beaver were essentially wiped out by intense Euro-American demand for beaver fur hats, although the species has made a comeback in the Northeast in the very recent past. Today in Sudbury, beaver activity is noticeable to everyone, although they are by nature a very shy animal, damming streams and wetland outlets to create calm ponds for their lodges and food supply. Beavers have always played a significant role in shaping the landscape, however, indigenous people viewed them as powerful agents of ecological transformation recognizing their contributions to water retention, soil fertility, and biodiversity. They were recognized as ecosystem engineers, capable of creating and maintaining wetland habitats that supported a diverse array of plants and animal species. Northeast tribes viewed them as integral members of the local ecosystem, worthy of admiration and reverence, as symbols of wisdom, perseverance, and adaptability. |

Beaver Lodge

When European settlers explored the fertile region defined by the Sudbury-Assabet-Concord River watershed during the early 1600s, members of the Nipmuc tribe, as well as the Nashoba and Musketahquid clans of the Massachusett tribe, lived throughout the area. Indigenous settlements are known to have existed in today’s towns of Concord, Littleton, Marlboro, Natick and Ashland – all within easy walking or canoeing distance of Sudbury. There is little written documentation for tribal groups living in the immediate Sudbury/Wayland vicinity, with the exception of a few men, including Karte and Tantamous, whose signatures appear on land sale deeds.

It is likely, however, that the Sudbury/Wayland area may have been a shared resource for regional inhabitants. Archeological sites and find spots indicate that occupation areas existed along the Sudbury floodplains and on the plateau above the river. Alfred Hudson, a 19th century historian, focuses specifically on Weir Hill, below Sherman’s Bridge:

| The very locality of this place is favorable for Indian occupancy. It is situated at a point of the river where…, at low water the river can be forded. On its opposite bank a hill extends almost to the stream, and on either side the meadow bank is hard, which is a circumstance rare on the river course. At this place tradition says there was an Indian fishing weir. |

An example of an Abenaki fish weir |

Hudson also comments on the town’s varied artifact collections and what they suggest about pre-Contact life and work (parenthetical explanations added).

Mortar and Pestle (Concord Museum) |

That these natural advantages were once improved by the Indians is evident from the number of relics which have been found in various localities. These consist of arrow and spear heads [hunting small and large game and fishing]; stone plummets [for fish nets]; chisels and gouges [woodworking]; mortars and pestles – implements for pounding and crushing corn; stone tomahawks or hatchets; and what may have been a stone kettle. Beside these, there have been unearthed by the plowshare small stones, that show the probable action of heat, and which may have been used for their hearthstones. |

| In addition to movable stone mortars, glacial erratics like the one pictured below were used to grind corn, grains, and nuts into meal or flour. |

Native American Communal Grinding Stone – Green Hill (SHS) |

In the “time before now”, when survival depended largely on available natural resources, tribal groups settled where food was near. This required adjusting to the seasons, through a regular annual cycle. This also required extensive shared knowledge of what we refer to today as the region’s ecology: Where are resources located? Why? What makes each one important to each other as well as to humans? How to maintain an equilibrium between human survival and resource depredation?

Living in this fragile balance resulted in very few long-term impacts on Sudbury’s lands and waterways. After 1638, this would all change.

Places to experience Sudbury’s Indigenous Landscape

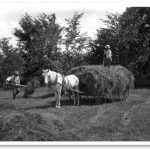

| Drive down Wolbach Road to get a sense of the fertile landscape and varied habitat indigenous people knew, used, and respected. Find more information on Wolbach Farm under Rural Town to Western Suburb. Click here for Wolbach Farm website and map. |

| The Grinding Stone can be found on the southeast slope of Green Hill, near the intersection of Singletary Lane and Green Hill Road. One of six known communal grinding stones located in Sudbury, this six‐foot diameter granite boulder has a large primary grinding surface. It was likely used for centuries by the local Nipmuc families before the arrival of the first English colonists. |

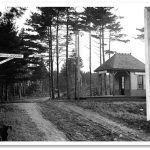

| At Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge at Weir Hill you can walk in the footsteps of indigenous people across the landscape they knew. The Sudbury unit includes trails through wetlands, woodlands, and fields. The site also includes an ADA-compliant boardwalk. You can hike over Weir Hill, a glacial drumlin, where Nipmuc anchored their fishing weirs. Visitors can also explore the Sudbury River via canoe or kayak. Click here for more information on the trails. Parking is available at 73 Weir Hill Road. |

| King Philip Woods holds historical significance. The land was named after Metacom, also known as King Philip, a leader of the Wampanoag tribe in the 17th century. The area surrounding King Philip Woods was once part of the traditional territory of the Nipmuc and Wampanoag people. The landscape would have provided abundant natural resources, including game animals, fish, edible plants, and materials for crafting tools and shelter. Additionally, the proximity of the Sudbury River would have offered opportunities for fishing and transportation. Parking is available on Old Sudbury Road across from Wolbach Road, as well as at a small gravel pull off on Water Row. Click here for additional information on King Philip Woods and a trail map. |

| Tippling Rock, being a prominent glacial feature, was a significant location to indigenous people. Some commentators have proposed that indigenous people would move a large boulder back and forth on top of the outcropping, an action referred to as “tippling”. The noise thus generated could be used to communicate over long distances. The height and broad exposure of the site also made it a good place for signal fires, either for indigenous or later Anglo watchers and offered an advantageous view of the countryside. A gravel parking area is available at 641 Boston Post Road. Click here for additional information on Tippling Rock including a trail map. |

Return to homepage or click on photos at top of page to explore other eras of change.