Rural Town to Western Suburb

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aerial view of trains at Union Avenue, undated (SHS) |

In 1870 and 1880 two railroads sliced straight through Sudbury’s flattest land. Speedy travel by train provided new work opportunities for farmers’ sons, who found urban jobs and left the family farm. Farm abandonment in Sudbury continued through the 1900s as later generations sold land that was worth more for residential development than for food production.

Traditional farm neighborhoods became available for housing, such as the flat Landham area. Some farms dating back to Sudbury’s earliest settlement were bought by urban professionals. Wolbach Farm, for example, was ‘gentrified’ with formal landscape design and new land uses.

Railroads

| “About 1870, the Framingham & Lowell Railroad was begun, and in the fall of 1871, the cars began passing through the town. A station was built at North and South Sudbury and at the centre. The one at South Sudbury was built a little northerly of the junction of the Sudbury and Marlboro and Framingham highways, and has since been moved….. In October, 1880, the first rails were laid at South Sudbury on the track of the Massachusetts Central Railroad, beginning at its junction with the Framingham & Lowell [rail]road.” (Hudson, History of Sudbury, 1889) |

America’s new and increasingly industrial economy redefined people’s ideas about what land was good for. Just as the profit demands of large-scale industry downstream at Talbot Mills in Billerica had damaged the water meadows in Sudbury (see Smooth River, Small Falls page), so the possibility of profitable railroad transportation for goods and passengers partially damaged, and certainly interfered with Sudbury’s agricultural land.

Take a look at the 1895 USGS map section below. Look at the land contours between “South Sudbury” and “Wayside Inn”. The age-old indigenous trail and 17th century Boston Post Road were laid out as close as possible to the edges of land that might be useable for planting or occupation – next to wetland to the south; then next to the steep slopes of the Nobscot Hill complex as the road passed over Hop Brook and out of town.

1894 USGS Section – Sudbury

Now look at where the railroad lines were located. The north-south line labeled “(Old) Colony Railroad” drove as straight as it could through the town. It was the first American railway designed to connect industries on a north-south line, running from Lowell to Framingham, then to New Bedford on the Massachusetts south coast. It wasn’t going to waste time or money meandering around natural features if it didn’t absolutely have to. [see Friends of the Bruce Freeman Rail Trail]

The Massachusetts Central Railroad [see Mass Central Rail Trail for more background] aimed to do the same thing from Northampton in western Massachusetts to Boston in the east. Along the way it could load products from significant industrial towns like Ware, Fitchburg, and Ayer; plus milk and agricultural products from dozens of small towns on the route. Not coincidentally, it could also transfer goods manufactured in Lowell from the Old Colony Line trains, for a straight shot into Boston.

Land for Food or Houses?

The open farmlands of Sudbury’s landscape presented an attractive opportunity for residential development due to their relatively flat terrain, fertile soils, and scenic rural landscapes. As urbanization and population growth increased demand for housing, developers looked to these agricultural areas as prime sites for residential expansion. Additionally, the proximity of farmlands to existing infrastructure such as roads, utilities, and services made them more cost-effective for development.

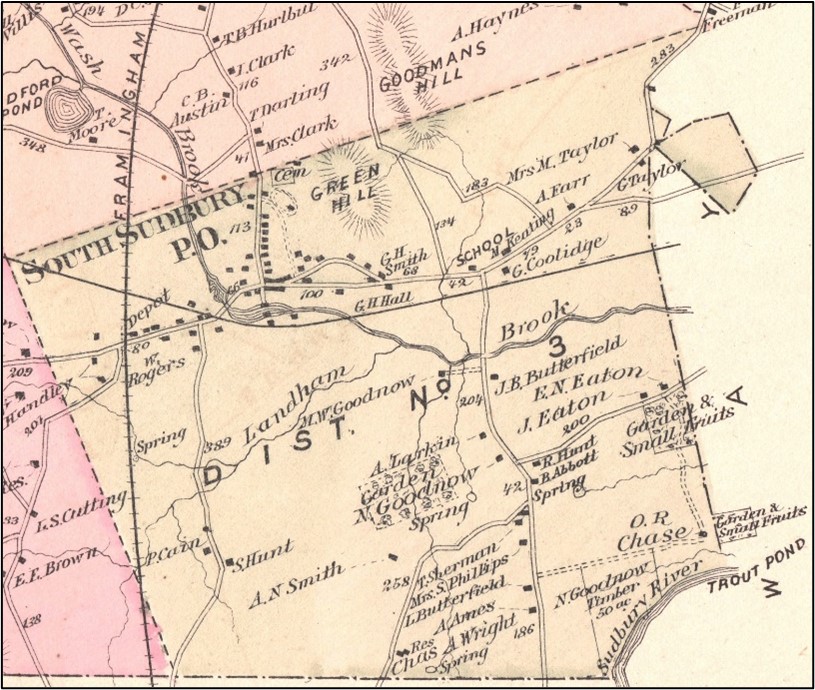

Take a look at a close-up from an 1875 atlas – this is the part of Sudbury that used to be referred to as “Landham”.

Map of Maynard and Sudbury from Beers Atlas of Middlesex County 1875, South Sudbury section

This low-lying, flat area is outlined in large part by wet meadows and the brook that flows east under various names to the Sudbury River. Fresh water springs are noted across the area, as are a variety of agricultural enterprises (“Garden” and “Garden & Small Fruits”) that grew plants and produce on a commercial scale in the rich soil of this glacial outwash plain. Even a specified 50 acres of “Timber” (lower right) indicates the commercial importance of this area’s land and water resources. A dozen houses are indicated in all of Landham.

Today, nearly 150 years later, the entire Landham area, with the exception of development along Route 20, permanent wetlands, and land set aside for water supply protection, has been subdivided into residential lots – most of them less than 2 acres – plus a handful of institutional buildings such as churches.

Map section shown below was released by the Town of Sudbury in 2024.

What has this meant for Sudbury’s land and natural resources?

The results of such widespread residential development were bound to be economically beneficial for the Town. A 1947 Town Finance Committee report predicted:

| “Sudbury is likely to grow more in the next ten years than in any equal period of time in the Town’s long history. New homes will be built and additional land will be used and improved. The development will bring new revenue and also new and greatly increased expenses.” |

As the Committee predicted, Sudbury saw its income from real estate taxes increase from $92,000 in 1946 to $410,000 in 1956 – an increase of almost 350% in only ten years! The long-term impacts on Sudbury’s land and natural resources were not all so beneficial.

Profound changes in Sudbury’s landscape occurred due to rapid residential development. During this period, the once predominantly rural and agricultural character of Sudbury underwent a significant transformation as vast tracts of farmland and open space were converted into suburban neighborhoods and subdivisions, leading to the proliferation of single-family homes across the Sudbury landscape and a permanent shift away from its agricultural roots. The clearing of land for residential development resulted in the destruction of woodlands, fields, and wetlands. This fragmented habitats, disrupted local ecosystems, displaced wildlife, and diminished biodiversity.

More houses and more residents required additional building projects throughout town: such as schools, shopping centers, subdivision road networks, power and water extensions. Each of these projects disturbed land and waterways that had essentially remained unchanged through 300 years of European occupation and thousands of years of indigenous use.

More impervious road and parking lot surfaces led to changes in drainage. Rainwater that previously soaked into the ground became “stormwater runoff” carrying pollutants such as fertilizers, pesticides, oils and sediment into nearby water bodies, degrading water quality and harming aquatic life. The list of harmful effects goes on: a strain on public water supplies; the significant spread of invasive non-native plant species and their associated destructive insects and diseases; and, increased air pollution from increased local energy consumption.

Working Farms to Country Estates

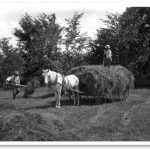

Sudbury’s most prized agricultural area – Landham – was located in the southeast corner of the town, but that did not deter colonial farmers from building sizable farms elsewhere. Most of Sudbury’s 18th and 19th century farm families practiced traditional mixed farming on their acres of forest, wet meadow, flat fields, and rocky hillsides. A hill with a gentle slope and a flat top, even if its soil was thin and rocky, provided a fine site for grazing livestock. A few acres of wet meadow along a brook produced a valuable crop of hay to feed dairy cows over the winter. By the 19th century hay and dairy products were Sudbury farms’ most valuable commercial goods, and some farmers made small fortunes raising and trading livestock. Any farm might also produce maple syrup, cranberries, apples, and (every couple of decades at least) a good haul of timber in high demand for the building boom that was happening in industrial towns like Framingham and Maynard, right next door.

The problem with this mix of products was the amount of labor involved in every one of them, and the often extreme challenges of the work. Much of it was traditionally “man’s work” – maneuvering a plow hauled by two 2-ton oxen who wanted to go in different directions; felling and stacking and driving a team of six work horses as they dragged a sledge of pine tree trunks through snow. Manuring fields, mending fences, keeping the barn water-tight, dealing with sick animals and calving season – all required a strong work force with no guarantee of continuing employment after harvest. This situation was more or less manageable as long as an aging farmer had the unpaid labor of strong sons.

Between the middle and the end of the 19th century, however, circumstances worked against stable farm life in southern New England. Starting as early as the opening of the Ohio Territory for settlement, and combined with a demand for industrial workers, and the Northeast’s terrible Civil War losses, many Sudbury farmers let fields go fallow and orchards revert to wild for want of labor.

Bent Farm to Wolbach Farm

What is known today as Wolbach Farm, headquarters of Sudbury Valley Trustees, was one of the farms that fell on hard times despite the efforts of Thomas E. Bent, last of four Bent family generations to farm on the site. He managed and worked on the farm until the age of 77, whereupon he sold its 85 acres, buildings and farm equipment to an unmarried Sudbury woman. At her death in 1914, the property changed hands again, this time purchased as a wedding present for Anna Wellington on her marriage to Dr. S. Burton Wolbach.

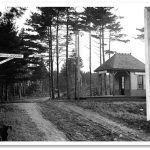

At first the newlyweds lived in a Boston townhouse much of the year, while they commissioned the transformation of Bent Farm from a working agricultural enterprise to a rural family retreat; a weekend and holiday place where they could enjoy an active outdoor lifestyle and also escape city heat and dangers, such as the influenza epidemic that shut down Boston in 1918. Dr. Wolbach was an infectious disease specialist, so it may have been at his urging that one of the earliest new constructs on the site was a large double greenhouse to provide fresh vegetables at a time when many markets were closed.

A November 1917 advertisement in The New Country Life magazine cites an exemplary greenhouse complex. These greenhouses of Mr. W. H. Wellington, at South Sudbury, Mass. are an interesting example of planning well in advance.

The U-Bar Greenhouse company featured the Wellington-Wolbach greenhouse complex in a full page advertisement which, in addition to providing two photos of the greenhouses and potting shed, also comments on land use choices made by its owners and builders. Their advance planning made “their seeming hillside disadvantage [in]to a decided advantage by making a storage cellar under the first greenhouse.” The original Bent Farm buildings had been tucked up against a fairly steep uphill slope – normal practice for farms in this area, minimizing the interference of buildings on plowable land.

The walls of this greenhouse section are still standing. They are a 20th century version of the stone-lined dugout root cellars found throughout New England.

Another caption on the photos notes that the lower greenhouse was used to grow vegetables, while the upper one was used as a grapery and a general plant house. The upper one was closer to the main house and likely visible from it. It was designed to be more ornamental, echoing a design trend toward large greenhouse structures popular at the time on gentlemen’s country estates, intended to serve primarily as hothouses for exotic plants and delicate vines.

Besides the greenhouse, one large barn replaced the two Bent-era barns and managed to incorporate – in one building – all of the needs of livestock, farm tools, machinery, and motor vehicles. Six stanchions shared the south end of the barn with the horse stalls. They were for milking cows. It would seem the Wolbachs faced the challenges of wartime America by incorporating milk cows into their menagerie that included a stable of riding horses and hunting dogs.

Many other land changes took place over the Wolbach years. On one hand, the old farm property saw swimming pools and entrance plantings installed in a landscape that incorporated heirloom apple trees plus a partially realized woodland garden based on Olmsted Brothers plans.

More recently, the whole property was bequeathed to conservation organizations by John Wolbach. Downslope from the Wolbach buildings, 39 acres became part of the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. In the early 2000s, 53 acres were bequeathed to Sudbury Valley Trustees, resulting in the organization locating its headquarters here.

Wolbach Farm, 2023

The 53-acre Wolbach Farm as we know it today includes wet meadow and fields, white pine stands, mixed deciduous forest, seepage wetlands, and an intermittent stream as well as the remnants of professionally landscaped grounds surrounding a main house, caretaker’s cottage, barn, and greenhouse. It is adjacent to a marsh and extensive red maple/shrub swamp in the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge owned by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Wolbach Road divides the upland buildings from their lower fields, barn and cottage. A cart path heads up through the forest behind the house. Stone walls bound the north, west, and southern edges of the property. Old Sudbury Road (Route 27) forms its property boundary to the east.

Where to explore

| Wolbach Farm, 18 Wolbach Road, off Route 27; look for SVT sign. Parking available. Lewis Trail: 1.2-mile loop walk. |

| From Route 20, turn south on Landham Road, and drive across the marshes. Take any side road after that to see the overlay of housing on flat agricultural land. |

| Landham Brook Conservation Land: In 2011, the Landham Brook Conservation Land, formerly known as Johnson Farm, was slated to be converted in 120 units in 10 buildings scattered throughout this approximately 35-acre parcel (14 acres of which are classified as wetlands). The proposal was denied by the Town, and in 2012 a 40B Comprehensive Permit was submitted for 56 units. This proposal, though approved by the Conservation Commission, had been appealed to the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and in November 2013, DEP denied the project. In 2014, the developer submitted a third proposal for 60 units in seven buildings.

After much negotiation with the developer, in 2015, the Town and SVT purchased and preserved 33.5 acres of the Johnson Farm from being developed. The property abuts over 200 acres of preserved open spaces owned by SVT (Lyons-Cutler Conservation Land), Sudbury Water District, and U.S. Fish & Wildlife. The old farm fields now serve as native pollinator meadows. A small gravel parking area is available on Landham Road just past Stagecoach Drive. Click here for a trail map of Landham Brook. Click here for a trail guide of Lyons-Cutler. |

Landham Brook Conservation Land (SCC)

Return to homepage or click on photos at top of page to explore other eras of change.