Sudbury Now: Conservation, Restoration, Resilience

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

White-tailed Deer (Russell Place)

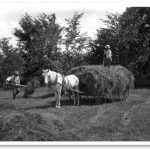

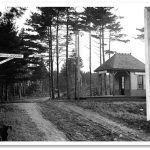

| “Maximum development – agricultural land conversions and industrial hydropower development – occurred in Thoreau’s generation. By the time of his death, virtually every square inch of the land had been transformed in some way: rock to quarry, river to canal, brook to millstream, wood to fuel, land to pasture, and field to cropland. The entire [Sudbury River] valley had become a network of dams, canals, turnpikes, railroads, factories, town streets, and country roads.” (Robert M. Thorson, The Boatman, 2017 |

| Three hundred years after European colonists began transforming the landscape, a growing number of Americans became concerned about what was being lost in the process. Public and private organizations began directing funds to the protection of rare sites and essential resources. National and statewide organizations formed to support this effort. On the federal level, the establishment of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in 1871, and the National Park Service in 1916, marked the government’s new commitment to preserving natural resources. In Massachusetts, The Trustees of Reservations (1891) and the Massachusetts Audubon Society (1896) drew attention to endangered wild lands and wildlife, beginning a long success story of protecting the nature of Massachusetts.

Attitudes toward land protection in Sudbury have evolved significantly over time as well, reflecting the shifting national attitudes towards conservation, development, and environmental stewardship. As the town experienced rapid suburbanization and population growth in the mid-20th century, concerns about the loss of open space, habitat fragmentation, and environmental degradation began to emerge. This led to a greater recognition of the importance of preserving Sudbury’s natural landscapes and biodiversity for future generations. Today, there is a heightened awareness of the value of land conservation in Sudbury, with a growing emphasis on protecting ecologically significant areas, preserving wildlife habitat, and maintaining water quality. Local organizations, such as Sudbury Valley Trustees (SVT) and the Sudbury Conservation Commission, play crucial roles in advancing land protection efforts through land acquisitions, conservation restrictions, and advocacy for responsible land use practices. This shift in perspective underscores a broader cultural shift towards valuing and prioritizing the preservation of natural landscapes and environmental resources.

Land Protection Partners Sudbury Valley Trustees In 1953 a group of local residents set out to protect the open spaces of Wayland from a post-war development boom. While other conservation groups focused on tracts of land covering hundreds of acres, SVT’s founders set their sights on the smaller parcels of wetlands, farmlands and open space that dotted the region around the Sudbury River. Since that time the organization has extended its range of commitment to all the communities in the watershed. SVT now owns or holds conservation restrictions in 25 of the 36 municipalities around the Sudbury, Assabet, and Concord Rivers. In 2002 SVT repurposed a house, barn, and 53 acres of land on Wolbach Road in Sudbury as its permanent organizational headquarters. Today SVT collaborates with public and private organizations and citizens’ groups to protect land; to restore wildlife habitats damaged by human activity and climate change; replace invasive non-native plants with native species; conduct prescribed burns, and sponsor a range of public programs to engage neighbors with the region’s natural areas. Town of Sudbury Conservation Commission The creation of the Sudbury Conservation Commission in 1962 marked a pivotal moment in the town’s environmental stewardship and commitment to preserving its natural resources. Established in response to growing concerns about the impacts of development on Sudbury’s environment, the Conservation Commission was formed to protect and manage the town’s wetlands, water resources, and open spaces. Its creation reflected a recognition of the importance of conservation efforts in maintaining the ecological health and quality of life in Sudbury. In 1972 the Commission was mandated to enforce the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act, to oversee wetlands protection and environmental management at the municipal level. This regulatory role has played a crucial role in safeguarding Sudbury’s natural landscapes from adverse effects of development. In 1998 the Conservation Commission enacted the Sudbury Wetlands Administration Bylaw which stands as an additional crucial protection for Sudbury’s environment since, by requiring permits for any alterations to wetland resource areas and their Adjacent Upland Resource Areas, the Bylaw ensures that construction projects adhere to stricter environmental standards to minimize adverse impacts on wetland ecosystems and their associated habitats. The Sudbury Wetlands Administration Bylaw serves as a model for responsible environmental stewardship for other communities to follow. The establishment of the Sudbury Conservation Commission reflects the town’s commitment to sustainability and responsible land use planning. By safeguarding Sudbury’s natural resources and promoting environmentally sound development practices, the Commission plays a vital role in ensuring the long-term health and resilience of the town’s ecosystems. Its efforts not only benefit current residents but also contribute to the preservation of Sudbury’s natural heritage for future generations to enjoy. The Commission works closely with other town departments, environmental organizations, and community groups to promote conservation awareness, conduct environmental research, and implement habitat restoration efforts. Its work encompasses a wide range of activities, including wetlands protection, water quality monitoring, land acquisition, and environmental education and outreach. OARS (Organization for the Assabet, Sudbury, and Concord Rivers) and Hop Brook Protection Association These two local organizations have played integral roles in improving water quality in the Sudbury River and Hop Brook. OARS’ mission is aimed at restoring and protecting the health of the Assabet, Sudbury, and Concord Rivers, which together form the riverine ‘backbone’ of the region. Through collaborative efforts with local communities, government agencies, and other conservation groups, OARS has conducted water quality monitoring, advocated for pollution reduction measures, and implemented restoration projects to mitigate the impacts of pollution and habitat degradation. Similarly, the Hop Brook Protection Association has focused its efforts on preserving and enhancing the water quality of Hop Brook and managing water chestnut in Hop Brook’s Grist, Carding, and Stearns Ponds, all former mill ponds. Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge The GMNWR, a federal conservation property managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, was established in 1944 in Concord, with its Sudbury extensions acquired during the 1960s. Today it protects 3,863 acres that consist primarily of waterways and wetlands, in Concord, Sudbury, Bedford, Billerica, Lincoln, Carlisle, Wayland and Framingham. Legislation for the refuge defined its purpose as providing “an inviolate sanctuary, or for any other management purpose, for migratory birds” (Migratory Bird Conservation Act). At the same time, the Refuge Recreation Act further defined all the U.S. Fish & Wildlife refuges as “suitable for … incidental fish and wildlife-oriented recreational development, …the protection of natural resources, and … the conservation of endangered species or threatened species…” The Great Meadows Eastern Massachusetts National Refuge Complex is headquartered on Weir Hill Road, in Sudbury. It includes upland hiking trails and a river-level ADA-accessible boardwalk. The headquarters building also provides a broad view of the river meadow from its ramp-accessible elevated deck.

Restoration Efforts Trying to restore a landscape – to reverse the loss of natural value due to human use or misuse – often takes decades. Today, for instance, a river-view platform at Weir Hill, part of the GMNWR, presents a calm vista of cattails and button bush, but only after this portion of the Sudbury River was declared a federal Superfund site and the river itself dredged. (See below for more on the Nyanza Chemical clean-up effort) In Sudbury, several other specific environmental improvements have been implemented to enhance the town’s ecological health and quality of life. One notable example is the restoration of impaired water bodies, such as the Sudbury River, which has been the focus of extensive efforts to improve water quality and habitat conditions. Through collaborative initiatives involving local stakeholders, government agencies, and environmental organizations, pollution sources have been identified and targeted for remediation, while restoration projects have been undertaken to enhance habitat and increase biodiversity. Sudbury has also implemented initiatives to promote sustainable land use practices and mitigate the impacts of residential development on the environment. Through zoning regulations, land use planning, and smart growth principles, the town has sought to balance development needs with conservation goals, preserving open space and natural resources while accommodating growth and maintaining the town’s rural character. Efforts to promote green building practices, energy efficiency, and stormwater management have also been undertaken to reduce environmental impacts associated with residential and commercial development, fostering a more sustainable and resilient built environment in Sudbury. Today, the beaver is once again our partner in conservation. Beavers, which were once nearly extirpated from the state due to overhunting and habitat destruction, have made a significant comeback. Efforts to protect wetlands and waterways have played a crucial role in supporting the recovery of beaver populations. Additionally, changing attitudes towards wildlife conservation and the recognition of the ecological benefits that beavers provide have led to greater tolerance and even appreciation for this species. However, it continues to be essential to strike a balance between promoting the recovery of the beaver population and addressing potential conflicts with human activities, such as flooding of roads and agricultural lands. Techniques like flow devices and beaver deceivers are often employed to manage beaver activity in areas where conflicts arise while still allowing them to contribute to ecosystem health. Despite the significant changes wrought by development, efforts to restore and conserve Sudbury’s natural landscapes are ongoing, driven by a growing recognition of the importance of ecological stewardship and cultural heritage. Conservation initiatives, land restoration projects, and sustainable land management practices aim to mitigate the impacts of human activities and improve the resilience of Sudbury’s lands for future generations. These efforts reflect a commitment to honoring indigenous perspectives, restoring natural ecosystems, and fostering a deeper connection to the land among our residents. |

| Where to Explore |

| Hop Brook winds its way through approximately nine miles of Sudbury. It’s Hop Brook you pass when you drive along Wayside Inn Road; it’s Hop Brook you drive over twice as you drive up Dutton Road; it’s Hop Brook you pass on Peakham Road near Blueberry Hill Road; and it’s also Hop Brook that you traverse on Landham Road. It is even Hop Brook that the railroads – now the rail trails – cross over.

Today you can glimpse the impact of Sudbury’s widest-reaching conservation effort at the Landham Road bridge, where broad marshes along Hop Brook and the Sudbury River are filled with wildlife, all protected by a partnership of the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, the Town of Sudbury and SVT. Walk along Hop Brook Marsh to a bridge over the brook to see natural diversity conserved by the Town of Sudbury to protect the town’s water supply. Not long ago, these areas were much less appealing and healthy. As residential and commercial development expanded in the area, impervious surfaces such as roads, parking lots, and buildings increased, leading to greater stormwater runoff and pollution entering Hop Brook. This influx of pollutants, including sediment, nutrients, and contaminants from roadways and developed areas, has degraded water quality and impaired aquatic habitat. Additionally, alterations to the stream channel and surrounding landscape, such as culverting and encroachment into riparian buffers, have disrupted natural hydrological processes and reduced the stream’s ability to support diverse aquatic habitats and species. These cumulative impacts of development underscore the need for proactive measures to restore and protect Hop Brook’s ecological integrity, including stream-restoration projects, stormwater management, and land conservation efforts aimed at preserving riparian buffers and minimizing further degradation of the watershed. Water chestnut, an invasive aquatic plant, poses a significant ecological threat to Hop Brook’s mill ponds: Grist, Carding, and Stearns Mill Ponds. The invasive plant outcompetes native species for sunlight, nutrients, and space, disrupting ecological balance and diminishing biodiversity. Ongoing efforts to control and eradicate water chestnut are essential for preserving the health and vitality of the aquatic ecosystem and ensuring continued enjoyment of the natural beauty of the area by visitors and residents alike. |

| The best place to see the Sudbury River in Sudbury is at Sherman’s Bridge on Lincoln Road. This can be seen by car or on foot. A small parking area is available in Lincoln just over the bridge.The impact of Nyanza Chemical in Ashland, MA, on the Sudbury River has been profound, with decades of hazardous waste disposal resulting in widespread contamination and ecological damage. The discharge of toxic chemicals such as mercury, arsenic, and lead into the river has significantly degraded water quality and threatened the health of aquatic ecosystems. The accumulation of pollutants in sediment and water has posed risks to fish and wildlife populations, as well as to human health through potential exposure pathways. The legacy of contamination from the Nyanza site has had far-reaching impacts downstream, affecting water users, recreational activities, and the overall ecological health of the Sudbury River watershed.

Efforts to restore the Sudbury River from the impacts of Nyanza Chemical have been ongoing, involving a combination of remediation, monitoring, and restoration initiatives. Remediation efforts have focused on containing and removing contaminated sediments, reducing pollutant loads, and restoring natural hydrological processes to minimize further environmental degradation. Monitoring programs assess water quality, track contaminant levels, and evaluate the effectiveness of remedial actions over time. Restoration efforts have included habitat enhancement projects, riverbank stabilization, and community engagement initiatives aimed at raising awareness about the importance of protecting and preserving the Sudbury River ecosystem. While progress has been made in addressing the impacts of the Nyanza site, continued vigilance and collaboration are essential to ensure the long-term health and resilience of the Sudbury River and its surrounding environment. |

|

Sudbury River at Sherman’s Bridge (SCC)

| The Memorial Forest Restoration Project stands as a testament to the community’s commitment to environmental stewardship and conservation. In the face of quickly changing climate conditions, efforts to encourage the resilience of Sudbury’s varied ecosystems are increasing. A prescribed burn within the 900-acre Desert Natural Area (which includes SVT’s Memorial Forest) has served to support its pitch pine-scrub oak community, among the most endangered ecosystems in the country. Many of the Desert’s plant and animal species are adapted to fire and depend on occasional fire for survival. This project, initiated by the SVT and other conservation landowners – and supported by volunteers and community members – is working at removing invasive species, rehabilitating overgrown habitat, and reintroducing native vegetation to promote biodiversity and restore the forest’s resilience. |

|

Desert Natural Area Controlled Burn (SVT)

| Davis Farm Pollinator Meadow:

This initiative, spearheaded by the Conservation Commission and supported by community volunteers, transformed a former forest into a thriving ecosystem teeming with native wildflowers, grasses, and other pollinator-friendly plants. The meadow not only provides essential food and shelter for bees, butterflies, and other pollinators of local wild plants and food crops, but also serves as a valuable educational resource for visitors, providing an up-close look at the pollinators’ vital role in sustaining healthy ecosystems. Parking is available at Davis Farm on North Road, just past the Bruce Freeman Rail Trail as you head towards Concord. |

| The east-west Mass Central Railroad and the north-south Framingham and Lowell Railroad, once essential arteries of transportation and commerce through the heart of Sudbury, also wreaked havoc with the town’s environment through extensive deforestation and wetland destruction. Coal ash, smoke, and oil spills from the operation of steam locomotives and maintenance facilities degraded air and water quality along Sudbury’s railroad corridors and in nearby communities.

As railroads became unprofitable to run, the two railways with their track, ties and infrastructure fell into disrepair, leading to additional environmental concerns. Sudbury, however, recognized the potential for repurposing these corridors and worked for decades to extend the Bruce Freeman Rail Trail from Lowell through Sudbury. Meanwhile the east-west line is being transformed into the Mass Central Rail Trail through a separate collaborative effort between Eversource and the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. The adaptive reuse of railroads as rail trails has emerged as a popular and effective strategy for revitalizing transportation corridors and enhancing community livability. By repurposing underutilized transportation corridors as linear parks and recreational trails, rail trails offer safe and accessible opportunities for people of all ages and abilities to enjoy Sudbury’s changing lands. The Bruce Freeman Rail Trail is anticipated to open in June 2024, closely followed by the Mass Central Rail Trail in 2025. These corridors will connect many of the sites identified in this guide, providing an ADA-accessible way to explore these locations. |

| “As from the far-reaching and silent past survive the signs of its many changes, may we take knowledge that these are indicative of changes yet to be.” (Alfred S. Hudson History of Sudbury, 1889) |

Return to homepage or click on photos at top of page to explore other eras of change.